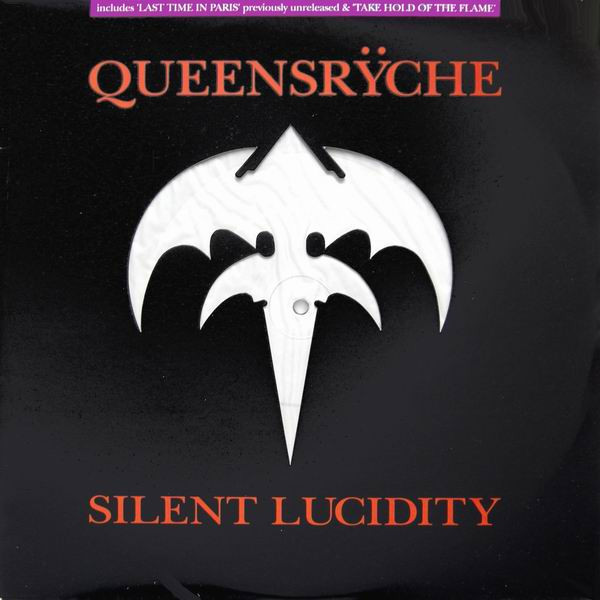

| Silent LucidityQueensrÿche |

Writer(s): Chris DeGarmo (see lyrics here) Released: February 1991 First Charted: January 26, 1991 Peak: 9 US, 15 CB, 13 GR, 15 RR, 11 AR, 18 UK, 7 CN, 1 DF (Click for codes to singles charts.) Sales (in millions): -- Airplay/Streaming (in millions): -- radio, 54.4 video, 67.09 streaming |

Awards:Click on award for more details. |

About the Song:The progressive heavy metal band Queensrÿche formed in 1982 in Bellevue, Wasington. After two gold albums, the band’s third release, Operation: Mindcrime was a platinum-selling concept album buoyed by the album rock hits “Eyes of a Stranger” and “I Don’t Believe in Love.” Still, the band had yet to crack the top 40 in the United States with one of their albums. That changed with 1990’s Empire, a triple-platinum release which reached #7 on the album chart. At first it appeared it would follow a similar trajectory as its predecessor. “Empire” and “Best I Can” were both top 30 hits on the album rock chart, but didn’t dent the Billboard Hot 100. However, the album’s third single, “Silent Lucidity,” propelled the band into new territory. Not only did it top the album rock chart, but it became the band’s first (and, so far, only) Hot 100 hit – climbling all the way to the top 10. The power ballad was sung by the band’s lead singer, Geoff Tate, with an emotive quality that recalled Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb.” It was written by the band’s guitarist Chris DeGarmo, who wrote or co-wrote most of the songs on Empire. He was inspired by the book Creative Dreaming, which explains how to tap into one’s subconscious mind. SF Tate said that even though he didn’t write it, “I love that song. I think it’s a beautiful, beautiful piece.” SF The song was a departure from the band’s more metal leanings, even incorporating cello. It was built on vocals and acoustic guitar with other instrumentation only being added in the last week the band worked on the record. The producer, Peter Collins, initially didn’t want to release it because he didn’t think it was developed enough. SF The song received Grammy nominations for Best Rock Song and Best Rock Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group. Resources:

Related Links:First posted 12/22/2022. |